Alison Aminzadeh

Hisham Shaban Galia traveled ten thousand miles to reach the United States, where he sought asylum.[1] Shaban was escaping the violence that plagued his home in the Gaza Strip, facing violence from both Hamas and Israel.[2] His asylum claim was denied because he failed to meet his evidentiary burden of producing documents to support his claim; he had represented himself pro se.[3] For the past sixteen months, Shaban has been held at an immigration detention facility in Arizona.[4] While Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has determined that Shaban cannot stay in the country, the fact that his home – Palestine – is no longer considered a state poses a problem: how can the U.S. deport someone to a state that, under the eyes of U.S. law, does not exist?[5] Shaban has since obtained counsel from the non-profit, the Council on American-Islamic relations.[6] His counsel, Liban Yousef, filed a habeas corpus petition for supervised release; if granted, this would allow Shaban to have the opportunity to work.[7] While the petition is still being reviewed, ICE released a “Decision to Continue Detention.”[8] Shaban fears that he will spend his life in the limbo of the detention center, having already spent over five hundred days there.[9] While his case appears unusual, the war-torn Gaza Strip is likely to produce more asylum seekers with similar backgrounds who will be difficult to deport under U.S. law.

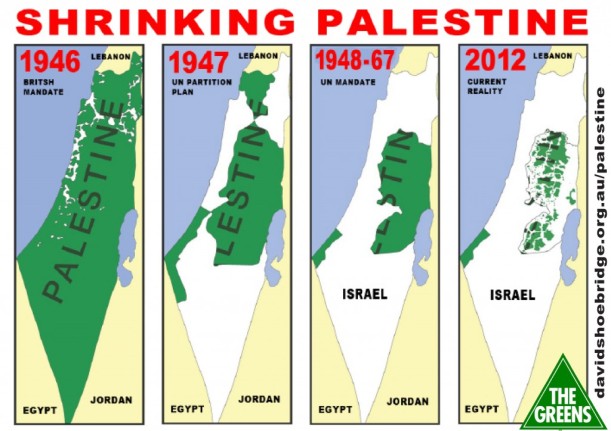

Palestine and Israel territory over the past 70 years

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states in Article 15 that everyone has the right to a nationality.[10] The history of Palestine is an interesting one: formerly seen as a “home for stateless Jews” in 1947, Palestine now finds itself in the reverse position: Israel has attained statehood, and Palestine has lost its status.[11]

There are four requirements for statehood.[12] First, there must be a population; this means that the alleged state must have people there.[13] Second, a state must have territory, meaning it must be based on some land.[14] Third, the state must have some government; in other words, there has to be some entity making the laws.[15] Finally, a state must have the capacity to enter into international relations.[16] This last requirement acts as a less-objective test and a safeguard for when the international community does not want to recognize a state. By not engaging with that would-be state, the international community can reinforce the idea that the entity is not a state.

There are about fifteen million stateless people worldwide, and the number is growing.[17] Based on the estimates provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Palestinians make up one-third of the stateless people worldwide.[18] Vicent Chetail writes that the Refugee laws for Palestinians are very strict.[19] While Shaban entered the U.S. for the legal purpose of requesting asylum, most Palestinian refugees are only able to enter other countries through illegal means.[20] In the United States, there are about 1,087 asylum seekers reported; however, given their lack of rights and access to resources, the number of asylum seekers in the U.S. is likely significantly greater.[21]

Shaban is not the first – nor will he be the last – Palestinian that the U.S. holds for deportation. When ICE was questioned on how Palestinians have been deported in the past, it asserted that it has coordinated with Israel, Egypt, and Jordan.[22] However, Shaban’s deportation officer gave him the option of being deported to Pakistan, Afghanistan, Malaysia, or Iraq.[23] Shaban has never been to any of these countries, and considered that this might be a threat; even so, he said he would go anywhere as long as he was no longer in detention.[24]

In addition to the practical conundrum that follows the attempt to deport a stateless person, there are also considerable legal concerns surrounding the international rights of people like Shaban. Article 31 of the UN Refugee Convention (1951) clearly states that no signatory shall impose penalties on refugees because of their illegal status, given the dire situations these refugees are fleeing.[25] The U.S., however, did not sign the Convention, but did sign the 1967 Protocol.[26] The Protocol appeared to retain the substantive portions of the 1951 Convention, and only removed the temporal and geographic restrictions, which focused mainly on events occurring in Europe.[27] Still, Chetail explained that the international community’s application of this Convention is problematic, as deportation should be used as a last resort and not a deterrent.[28] Shaban’s lawyer also alleges that the detention is unconstitutional, as it violates his client’s right to due process.[29] While statelessness is not a crime – in contrast, it is a mark of vulnerability – Shaban has remained in detention after being deemed inadmissible to the United States.[30]

Campaign to support the release of Hisham and Mounis Hammouda, also in detention

U.S. domestic law is not silent on the issue, either. The facts of Shaban’s case, as well as the cases of those like him, run directly contrary to the spirit of Zadvydas v. Davis.[31] The U.S. Supreme Court heard the facts pertaining to Kestutis Zadvydas’s detention. Zadvydas was born to Lithuanian parents in a German camp for displaced persons.[32] Neither Germany nor Lithuania would accept him upon deportation.[33] He was ordered to be deported due to his criminal record.[34] The removal period for aliens held in custody was ninety days.[35] After the ninety days passed, Zadvydas filed a writ of habeas corpus.[36] Justice Breyer, writing for the majority, expressed concerns over the constitutionality of a statute that would allow indefinite detention, writing that it is inconsistent with the Due Process Clause.[37] If one is to rely on stare decisis, it is evident that U.S. law does not permit holding Palestinians like Shaban indefinitely. Furthermore, during oral arguments, Justice Scalia had asserted that the burden of finding a country to be deported to lies with the petitioner.[38] Even if this is the standard for petitioners to meet, Shaban has already met it by wishing to be deported to his state of Palestine.[39] The conundrum lies in the refusal of the U.S. to recognize Palestine as a state, and its refusal to employ any alternative that would release Palestinian asylum seekers from indefinite detention.

To send a letter to Phoenix ICE Field Director Thomas Giles; ICE Director Sarah Saldaña, ICE Public Advocate Andrew Lorenzen-Strait, visit this website.

Alison Aminzadeh is a third year law student at the University of Baltimore. She is currently a Rule 16 attorney working on the Human Trafficking Project as a part of the Civil Advocacy Clinic. She is also a Senior Staff Editor for the Journal of International Law, and the former President of the Students Supporting the Women’s Law Center.

[1] John Washington, The US wants to deport this Palestinian – but first it would have to recognize Palestine, The Nation (Mar. 28, 2016), available at http://www.thenation.com/article/can-you-be-deported-if-you-are-stateless/.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Id., citing Universal Declaration of Human Rights , art. 15, Dec. 10, 1948.

[11] Washington, supra note 1.

[12] Motevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, art. I (Dec. 26, 1933).

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Washington, supra note 1.

[18] Id.

[19] Chetail is a professor of International Law at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Id., citing United Nations High Commissioner, Citizens of Nowhere: Solutions for the Stateless in the U.S., Refugees and Open Society Justice Initiative (Dec. 2012), available at http://www.rcusa.org/uploads/pdfs/UNHCR_OSJI_STATELESSNESS_REPORT.pdf.

[22] Washington, supra note 1.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 606 U.N.T.S. 267 (1951, 1967); States Parties to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol, UN High Commissioner on for Refugees (last accessed Apr. 10, 2016), available at http://www.unhcr.org/3b73b0d63.html.

[27] Haya Madanat, 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol, Hopes for Women in Education (Nov. 15, 2012), available at https://blog.hopesforwomen.org/2012/11/15/1951-refugee-convention-and-the-1967-protocol-by-haya-madanat/; Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, supra note 26.

[28] Washington, supra note 1.

[29] Id.

[30] Id.

[31] Id., citing Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678 (2001).

[32] Zadvydas v. Davis, 553 U.S. at 682.

[33] Zadvydas v. Davis, 553 U.S. at 682.

[34] Zadvydas v. Davis, 553 U.S. at 682.

[35] Zadvydas v. Davis, 553 U.S. at 682.

[36] Zadvydas v. Davis, 553 U.S. at 682; 28 USCS § 2241.

[37] Zadvydas v. Davis, 553 U.S. at 690; Washington, supra note 1.

[38] Washington, supra note 1.

[39] Id.