Esther-Jane Grenness

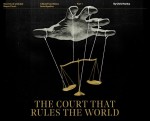

Mr. International-Lawyer sits down at his desk and boots up his laptop. As is his usual practice, he opens his email and sips his coffee while the morning sun streams pleasantly through his office window. He first peruses a Listserv email from the international arbitration committee of which he is a member. In that email, there are links to a four-part BuzzFeed investigation[1] examining investment treaty arbitration (ITA), sometimes referred to as investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). Mr. International-Lawyer’s interest is highly piqued, after all, he has served as arbitrator on several investment treaty tribunals.

The opening image of the BuzzFeed investigation’s first installment is enough to get Mr. International-Lawyer’s intellectual-battle-adrenaline pumping. He opens the articles one-by-one and reads on, glued to the pages, his indignation rising with each salacious detail. His fingertips rest on his warm coffee cup. Heat travels from his fingertips along the length of his arm, rushes up his neck, and boils over into his face. He’s almost, though not quite, livid. Having finished reading the exposé, Mr. International-Lawyer fires off a reply-all to the recipient list of the original email. The four-part BuzzFeed article, he argues, is full of wild claims and factual errors. Most graciously, Mr. International-Lawyer directs his colleagues to a factsheet[2] published by the International Bar Association (IBA), which contains point-by-point refutations of assertions made by critics of ITA/ISDS.

In the four-part BuzzFeed series, there are several examples of the very worst abuses of ISDS mechanisms available to foreign investors in the 3,000+ investment treaties dotting the globe. When discussing the role of the lawyers in these examples, one of Mr. International-Lawyer’s colleagues referred to the behavior as the “gamesmanship” in which less scrupulous counsel sometimes engage. While the stories are despicable, and an in-depth analysis of investment treaty arbitration is beyond the scope of this post, a couple things did stand out to me as I read two of the narratives in particular.

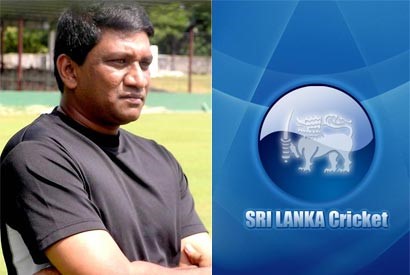

In the case of Sri-Lanka’s[3] bad oil-derivatives investment with a contract that was despicably one-sided, I’m quite struck at how little responsibility the BuzzFeed article placed on the executive who signed the deal. Conventional wisdom would say that one should have to pay the natural consequences of one’s own foolish actions, but the BuzzFeed article placed blame entirely on the bank for not doing the executive’s due-diligence for him. Any person heading a corporation, whether state-owned or not, should be at least marginally business savvy. The man who bound an entire nation was one who merely “dabbled” in the stock market. He admitted he didn’t completely understand what he was signing, yet he didn’t seek counsel from those who would understand the contract—lawyers. Even worse, he didn’t even read all parts of the contract.

Ashantha de Mel, the man who didn’t read the contract

While there certainly is an expectation of good-faith negotiations and sound policy reasons for protecting against unconscionable contracts, we’re talking about the head of a corporation here, not a sole-proprietor with little to no bargaining power. Advocating against allowing the bank to collect its money is disruptive to the rule of law—certainly in this instance at least. While morally despicable, law and morality don’t always intersect. Sri-Lanka wanted to block a legitimate enforcement of a contract because it deemed the contract “substantially tainted” and heartily disliked the manner in which the bank courted a signature. Sri-Lanka’s refusal to honor its foolishly-entered obligation is the very sort of arbitrary State action against which investment treaties are designed to protect. Unfortunately, sometimes such a reprehensible outcome is the unsavory result. But the burden lies on the signer to do his due diligence—especially one who signs on behalf of a corporation where a nation foots the bill. The burden should not be placed on a foreign investor to sift through another country’s policies on signatory authority to determine whether the person signing actually had the power bind the corporation over which he presides. An ordinary executive, acting in the ordinary course of business, usually has the authority to bind the company he heads. As such, the bank had a legitimate expectation and a legally vested right to realize its profits, ill-gained as they may have been.

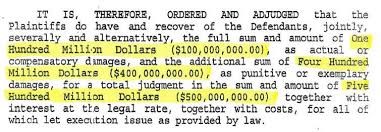

The Mississippi funeral home case[4] is a clear illustration of why investment treaties have provisions to protect foreign investors in the first place. It makes no difference here that the nation against whom the case was brought has a well-developed, usually fair justice system. When the law of the country in which a foreigner invests returns an unjust, clearly biased result, investors have recourse to remedy the wrong. Without such recourses for individuals against States, an investor would have to rely on his or her country of citizenship to intervene. Nations have a choice whether they will intervene on their national’s behalf or not. Investment treaty ISDS mechanisms provide individuals with standing against a Nation.

While the Canadian investor may certainly have been at fault and deserved to lose his case, he was entitled to a fair trial. Clearly, xenophobia, and outright hostility to the “other” element in the case prevailed. Had this been a situation in which the tables were turned and it was an American investor who received the same treatment in, say, Mexico, there would have been no sovereignty objection. The possibility of a foreign tribunal having the ability to question and overturn a sovereign nation’s determination would have been applauded. Only recently have developed countries been truly faced with having to answer for their own capricious actions, if any. Why is it that we now hear such loud protestations over threats to America’s sovereignty? Suddenly objecting to ISDS mechanisms we largely wrote, and founding the objection on grounds of sovereignty and the availability of sophisticated judicial systems is plain arrogance.

Mississippi case jury award

Notwithstanding the above defenses, the BuzzFeed investigation was truly appalling. As one reads the articles, questions churn within one’s mind: How on earth can this happen?!? Who would sanction such egregious abuses? Aren’t the provisions meant to incentivize infusions of much-needed capital into developing countries? Isn’t this a system that protects foreign investors from the vagaries of all-too-often capricious regimes? What went awry? Unfortunately, the answers, and the possible solutions that may reform a legitimacy-challenged system, are complex and difficult to boil down into a high-level, easily digestible summary. There are no easy approaches, but before we advocate for throwing out the kitchen with the sink, we need to consider the costs of dismantling an entire system.

<img height=”1″ width=”1″ style=”display:none” src=”https://www.facebook.com/tr?id=1772280696341572&ev=PageView&noscript=1″ />

Esther-Jane Grenness is an evening student in her fourth year of studies at the University of Baltimore School of Law. She graduated from the University of Baltimore in 2013 with a Bachelor of Arts in Jurisprudence and obtained her Associate of Arts from Howard Community College in 2001. Esther is a member of the International Arbitration Committee’s Investment Treaty Working Group of the American Bar Association’s Section of International Law. She also participated in the Mentorship program with the Women in International Law Interest Group of the American Society of International Law. In addition to her studies, Esther coordinates government procurement contracts in the mobility sales operations group for AT&T’s Global Business – Public Sector Solutions segment.

[1] https://www.buzzfeed.com/globalsupercourt

[2] http://www.ibanet.org/Article/Detail.aspx?ArticleUid=1dff6284-e074-40ea-bf0c-f19949340b2f

[3] https://www.buzzfeed.com/chrishamby/not-just-a-court-system-its-a-gold-mine?utm_term=.bjWJaxGwM#.lyzX4wNOq

[4] https://www.buzzfeed.com/chrishamby/homegrown-disaster?utm_term=.jtNOQjN3w#.bcN9yEN0K